-

Our Teams

- What We Do

- Careers

Reinventing the IPO Ticket: A Q&A with the New York Stock Exchange’s Archivist

The ‘first trade’ ticket has a storied place in history. While it has become the symbol of a company’s arrival on the global stage, its roots are more humble. Its history traces the evolution of more than a century of technological progress: from pencil on paper to light through fiber. To mark the debut of Citadel Securities’ new IPO ticket, we sat down with Peter Asch, the archivist at the New York Stock Exchange, to explore its storied past.

Is it true trading slips weren’t always used?

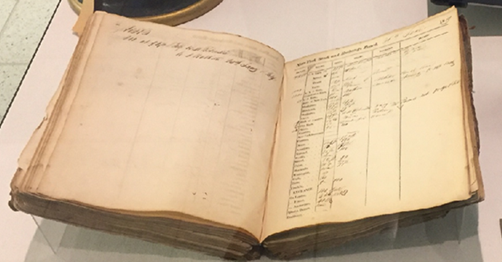

That’s right. Until the 1870s, the Exchange operated as a call market. The NYSE President would use a gavel to open and close trading for each stock one at a time. All transactions were recorded by the Exchange’s Secretary in the NYSE Sales Sheet Ledger.

Do we know when the first ticket debuted?

The exact moment isn’t known, but we can trace its roots back to the late 1800s. In 1865, the NYSE’s first permanent building was opened on Broad Street near the corner of Wall Street. It was remodeled in 1871 to allow for a continuous trading system, including the addition of six trading posts. Once those posts were established, the market maker model developed. That’s where a specialist would organize a crowd of brokers to trade in a single stock throughout the day.

When the current trading floor opened in 1903, the room had some of the newest tech, including the first room in Manhattan with air conditioning, 500 telephones, and a pneumatic tube system to send orders and market data throughout the building. The tools evolved over the past century, but the layout of the floor has stayed the same. The perimeter is filled with broker’s booths where house and independent brokers receive order flow to bring to the floor. At the center are the Designated Market Maker Posts where each stock is assigned to a single location.

How did the tickets actually work?

The trade tickets, which originally were just blank sheets of paper, were used to transmit information from the brokers to the market makers and then to return the executed orders. Over time, they got more standardized and each firm had their own propriety version. An order was received by a clerk in a broker booth and then delivered by a runner. Phone orders began to be displaced in 1965 when early electronic trading was first introduced. The mechanism for how tickets were used didn’t change until they were replaced by fully electronic order execution in the mid-2000s.

What else were the slips used for?

Clerks would also use tickets to fill out buy, sell, or cancel orders. It was stamped with the time using a punch clock to mark when the order arrived. The broker would sometimes take the order into the crowd and either hand the order to the market maker to be put into the book or transact the trade himself in the crowd.

Larger orders could be broken out into several transactions that the broker or specialist could record on the back of the original trade slips:

Brokers also carried a rectangular pad of generic tickets to send back parts of the trade as it was executed. For example a buy order of 1 million shares would take several hours and the broker would send back parts of the trade as transacted using these trade slips:

Remember, this is just how business was transacted for decades. Through the day thousands of these would just be dropped on the floor, including the very first trade of a company’s stock when it went public. There was a brief period when it became part of the IPO experience, but that went away as trading became more electronic.

And today?

It was only with the passage of time that people realized how historically important these slips were. Think of all the great companies that have built the world and driven us forward. They did so because of their ingenuity, but also because the markets let them access the capital they needed to realize their visions. That first trade ticket is literally the moment of price discovery; the point in time where buyers and sellers of stock first agreed on a company’s value. That sets the stage for the future to come, and enabling people to see it for themselves can only help inspire future entrepreneurs.

Tom Farley, President of the New York Stock Exchange, Reviews Citadel Securities New IPO Ticket in the Chairman’s Boardroom

- What We Do